If you're heading to EPL, there's a good chance you're there to borrow some of their materials. But who's deciding what's on the shelf? What about format? What's actually popular? By Janice Vis

Nine million dollars. What would you do with that money? Buy a house, or maybe a few? What if you used it to buy books? According to EPL’s Annual Report, that’s approximately how much money that Edmonton Public Library spent on books and library materials in 2015, a sum that accounts for almost one-fifth all library expenses.

Nine million dollars. What would you do with that money? Buy a house, or maybe a few? What if you used it to buy books? According to EPL’s Annual Report, that’s approximately how much money that Edmonton Public Library spent on books and library materials in 2015, a sum that accounts for almost one-fifth all library expenses.

But perhaps such a large number isn’t so surprising. EPL has twenty branches all stocked with books. New additions arrive all the time and the collection of digital items and services is expanding at a remarkable rate. Step into any library branch or spend a few minutes on their website and you’ll find the latest bestseller, library staff picks, award-winners, the latest superhero comic, and foreign language books – to name just a few.

And if the library doesn’t have your favourite book? You can ask them to buy it for you.

I took a stroll through Stanley A Milner to get a preliminary idea of the print at the EPL. I saw some kids’ books on display, but failed to recognize any of the titles. Why these particular books? I walked through the romance section; it’s almost entirely paperback. On the other hand, many non-fiction titles are oversized and hardcover. Again, why? And how does the EPL buy all these books? Who’s in charge? EPL’s website has some basic collections guidelines, but they are rather vague, citing everything from the duty to inform the public to provide entertainment to encourage a love of reading. Clearly, there’s more to it.

To get a better idea of how EPL chooses and purchases its materials I talked with Sharon Karr, the manager of EPL’s Collections Management and Access.

So, who’s deciding what ends up on the shelf?

According to Karr, EPL represents a fairly typical case for a library.

Collection is centralized by at one station, and decisions are made by four special collections librarians, each with a separate portfolio (an area of expertise) and budget. Not just anyone can become one of these collection librarians. “They are professionals,” Karr explains, noting that these individuals have earned a master’s degree in their field. “They all have a budget relating to their particular area... but they make all the decisions about what they will or will not purchase for their particular area.”

These collection librarians aren’t only deciding which titles to buy. “They decide on quantities, where it will go, and also format,” Karr explains. For example, one of the collections librarians is in charge of all the juvenile materials. This individual is specially trained in this area, chooses the titles that end up in the library’s children’s sections, decides whether to purchase these materials in hard or softcover, and decides how many titles need to be purchased initially.

If the title proves to be quite popular, more copies will be purchased in the future. Karr tells me that EPL has a five-to-one print-to-copy ratio, which means that “for every book that we have, we allow five holds on it. Once we have a sixth hold, we purchase a second book. So there are five holds to every copy. And that is true of every format... Think about it. Each person has the book, they sign it out for three weeks. Even if you’ve only got five holds on one copy, that’s still a three month wait.” I nod to myself, remembering waiting a few months to receive a copy of newest Star Wars film.

This print-to-copy-ratio may help limit wait times for library users, but it also means that EPL often needs to purchase popular titles in large quantities. “I think most people would be shocked to learn how high our holds queues can go,” Karr says. She notes how events like the Oscars can cause demand to skyrocket. “The Martian had close to fifteen hundred holds,” which means that EPL needed to purchase around three hundred copies.

What about Suggest-for-Purchase?

While collection librarians chose most of the material that ends up on EPL’s shelves, library card holders can also impact the collection by offering up to five suggestions each month. Karr highlights that the suggest-for-purchase option is “directly in the catalogue,” and therefore easily accessible. She also tells me that EPL receives “over fifteen hundred requests every single month. All of these requests go directly to a collections librarian.” I want to know how these suggestions are received, and she confidently tells me that “if it’s something our customers have asked for, if we can, and it’s appropriate, then we’ll normally buy it.”

There are some reasons that the library might not fill a suggestion. Karr acknowledges that there are some materials that the library simple can’t access. “If it’s out of print, then we simply can’t get it,” she explains. There are a few other reasons that a suggestion might be denied. For example, material that is too academic or falls out of EPL’s general guidelines may be passed over. The library’s budget also needs to be taken into consideration. However, Karr remains certain that suggest-for-purchase has a significant impact on the library’s collection.

How does EPL decide which format to buy?

At first, Karr’s answer is simple: “as a general rule we will buy in the format that our customers want.” However, there are a few more aspects to consider.

Availability plays a considerable role when buying different formats. “Generally we’re going to buy the hardcover – it’s released first,” Karr explains. If it follows in other formats, such as trade paperback or ebook, they’ll purchase those too. “If it’s a popular book, we’re going to buy it in every format,” she reiterates.

Of course, not all books are published in the same way. Karr notes that a lot of books are only published in paperback, and many materials are never made into ebooks, so EPL has to make due with what’s available.

Ultimately however, it all comes down to what’s going to be used, as Karr reminds me that “customer use informs where we’re going to buy things.” In other words, EPL will buy certain formats that have already proven popular with library users.

Remember all those romance paperback novels I noticed? Karr uses them as an example when discussing format with me -- and apparently, they’re on the way out. “Romance paperbacks used to be a huge thing in libraries. Like, people would come in and they would like take shelves of romance books... read through them in a night, then return them and get a whole bunch more,” she explains. However, things have changed. “Paperbacks for romance has declined extremely sharply in the last number of years… and that’s because of ebooks.”

Why? Ebooks give readers anonymity, allowing them to borrow and enjoy the material without feeling like others are judging them because of the title or the cover of the novel they’re reading. EPL has readily acknowledged and responded to this trend, as Karr informs me that much of the money that once paid for romance paperbacks is now “funneled in romance ebooks.”

What about usage? What library materials are currently popular?

It isn’t just romance paperbacks that are seeing less use. According to Karr, “paperbacks are going down in use, quite dramatically, and we’re seeing increases year to year of ebooks and other digital formats.”

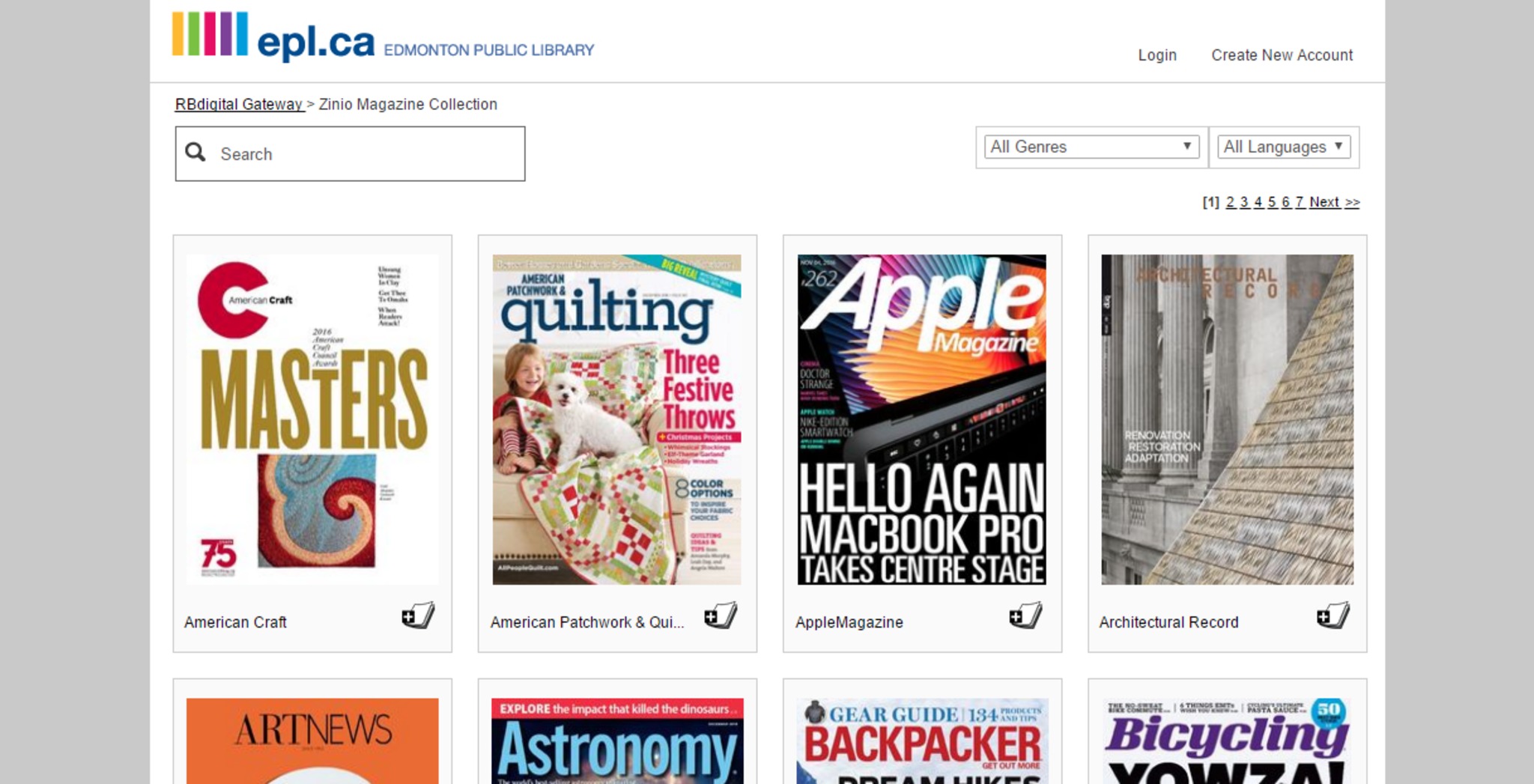

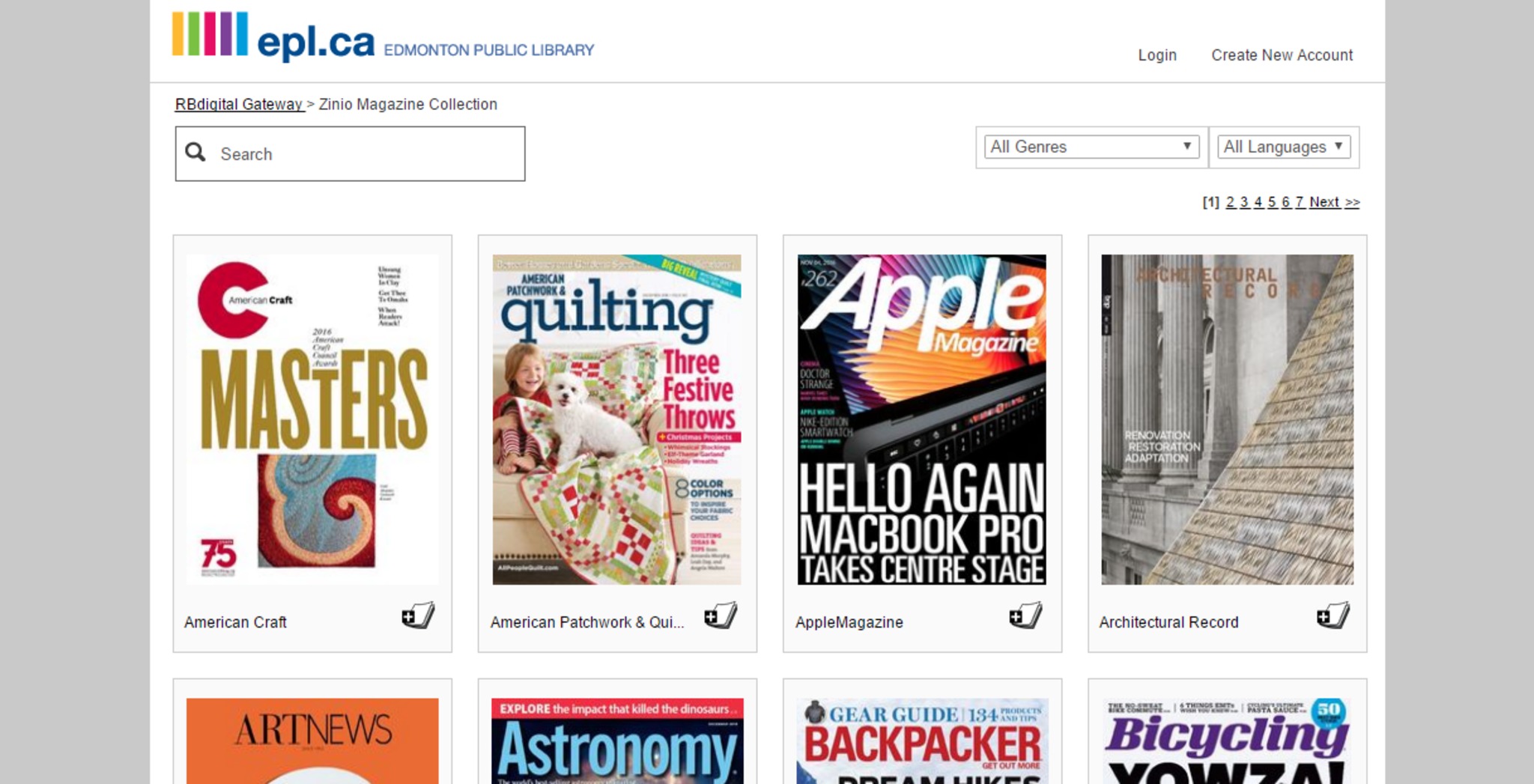

This trend isn’t limited to books. “Our print use for our magazines has also dropped pretty dramatically and we’re picking that up with digital content. We have Zinio (shown) and Flipster, two different kinds of platforms where we get full access.”

When I asked about library materials that are experiencing an increase in demand, print items don’t make the list. Instead, Karr informs me that “demand is going to build in formats that are much less traditional -- video games, either physical or online, streaming video and streaming music, downloadable video downloadable music -- those kind of things. A lot of money is going into those areas because there’s a lot more use there.”

However, this switch to digital content has some drawbacks. When asked about the challenges of collecting materials, Karr immediately went to the price of digital materials and services. She highlights the “diverse number of different kinds of digital resources” the library now offers to Edmontonians. “Our budgets haven’t gone up ten times, and the amount of material has,” she says.

Ebooks are particularly troublesome for libraries at the moment. Karr has even chaired a coalition aiming to bring awareness to this issue. “The licensing model libraries need -- that we use to purchase from our vendors -- can be extremely cost-prohibitive... There are some ebooks that will cost the average consumer ten, fifteen dollars to buy the book and the library’s being charged one hundred and fifty for one copy.” Notably, this single copy cannot be used by more than one person at a time. This can create a serious problem when considering more popular titles. “Whereas twenty copies of a book might cost us a hundred bucks, twenty copies of the ebook is going to cost us two thousand. So it’s been a real strain on our budget,” Karr explains.

Another problem facing EPL in regards to digital content is the exchange rate. “Our spending amount is highly dependent on how the Canadian dollar is doing,” Karr says. “A lot of [our materials] -- especially the digital resources -- we purchase from the US.”

What happens after EPL decides they want to purchase a text for the library? Where do they go?

“We do not buy our materials directly from publishers,” Karr assures me. “That would take a lot more than four people.” Instead, the EPL uses vendors. “We negotiate and sign contracts with them,” Karr explains. “We purchase directly through them...They work with publishers on [the library’s] behalf… and then they ship to us.” The library has two main vendors, one for print and one for audio-visual materials, and Karr tells me that the “vast majority” of what I see in EPL comes from these vendors.

Material selection happens from a digital catalogue. EPL collections librarians access “a selection list online, just like you would if you were buying off Amazon.” Not only do these vendors offer a selection list, they also “have alerts that come out… on publishers, on authors, and events” which might be useful to the library, as well as tools to help with purchasing decisions.

What are EPL’s policies for removing books?

The process of removing certain texts from the library’s collection is called “weeding.” With new materials always arriving at the library, old materials must be removed. EPL has a monthly “weeding schedule.” As Karr explains, “every single month, there’s something that we’re weeding for that month.” Library staff sort through the materials and remove items based on a certain criteria. As a general guideline, a text will be weeded based on “how long it’s been in the system, if it’s being used or not, and the relevancy.”

She provides a few examples; “if it’s non-fiction, then it’s after five years -- then that’s dated and it gets deleted. Or if it’s something that doesn’t age, then we’re basing it off of how grubby it is.” Notably, materials date at different speeds. Karr reiterates several times that “it depends on the area on how long it takes before something’s going to be weeded from the collection.”

Relevancy is a key concern for non-fiction collections. She cites the potential danger of keeping outdated science of medical textbooks, emphasizing that “misinformation is worse than no information.” Of course, paperback titles also date quickly. After only a year, they may “begin to look pretty ratty” and need to be replaced. But other material dates much slower, as Karr notes that “some of our older art history books are hard to replace -- they’re very expensive. They’re good for twenty years.” Unsurprisingly, an item’s use is also an important factor. A text will be removed from the collection if “it’s just not being used -- it’s not that something is wrong with it -- but we just need to make room for material that we know customers are going to use.”

Notably, a text will not be discarded due to its offensive nature. According to the collection guidelines, “EPL acquires a wide range of materials representing various points of view, including materials which may be considered controversial and offensive to some individuals.” Library users can object to any of the items at EPL and the staff will consider the complaint, review the material, and research critical reviews, but it's unlikely that EPL will scrap the title. This document shows the challenged materials from 1998-2015. Common complaints include sexual content and vulgar language. In a few cases, the library reclassified material (for example, moving a text from a juvenile to teen or adult section,) but these type of complaints never lead to the removal of a text. The select few complaints that resulted in removals related to the physical quality or relevancy of the material.

Conclusion

When one thinks about libraries, it's often the books that come to mind. And EPL certainly has books of all different shapes and sizes--books meant to entertain, books meant to teach, new books added to the collection, and then weeded out in due course. But collection at the EPL has grown beyond books, and continues to embrace digital materials and services.

As I talked with Karr, I repeatedly felt assured that EPL is connected to its customers' needs and wants and readily adapts to changing demand. Exactly how will demand change? How EPL will deal with the obstacles of an increasingly digital landscape? Perhaps in a few years a walk through an EPL branch will look much different than it does today.

Last Updated: Nov 11, 2016

Nine million dollars. What would you do with that money? Buy a house, or maybe a few? What if you used it to buy books? According to EPL’s Annual Report, that’s approximately how much money that Edmonton Public Library spent on books and library materials in 2015, a sum that accounts for almost one-fifth all library expenses.

Nine million dollars. What would you do with that money? Buy a house, or maybe a few? What if you used it to buy books? According to EPL’s Annual Report, that’s approximately how much money that Edmonton Public Library spent on books and library materials in 2015, a sum that accounts for almost one-fifth all library expenses.